John Garth

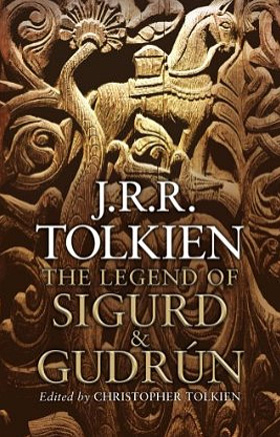

The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún

J.R.R. Tolkien. Edited by Christopher Tolkien. HarperCollins 2009.

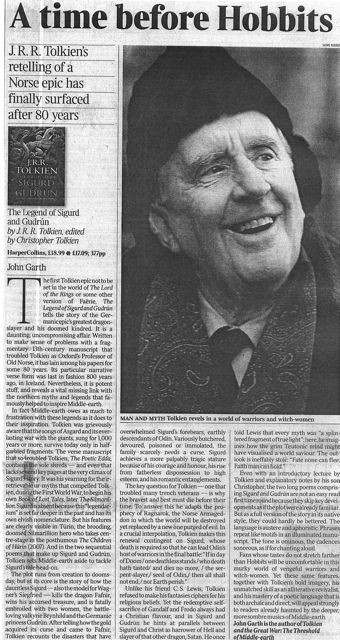

The first Tolkien epic not to be set in the world of The Lord of the Rings or some other version of Faërie, The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún tells the story of Germanic epic’s greatest dragonslayer and his doomed kindred. It is a daunting, uncompromising affair. Written to make sense of manuscript problems that troubled him as Oxford’s professor of Old Norse, it has lain among J.R.R. Tolkien’s papers for some 80 years. Its particular narrative verse form was last in fashion ten times that long ago, in Iceland. Nevertheless, it is characteristically potent stuff, and reveals at last a vital missing link with the Northern myths and legends that famously helped inspire Middle-earth.

The first Tolkien epic not to be set in the world of The Lord of the Rings or some other version of Faërie, The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún tells the story of Germanic epic’s greatest dragonslayer and his doomed kindred. It is a daunting, uncompromising affair. Written to make sense of manuscript problems that troubled him as Oxford’s professor of Old Norse, it has lain among J.R.R. Tolkien’s papers for some 80 years. Its particular narrative verse form was last in fashion ten times that long ago, in Iceland. Nevertheless, it is characteristically potent stuff, and reveals at last a vital missing link with the Northern myths and legends that famously helped inspire Middle-earth.

In fact Middle-earth owes as much to frustration with these myths and legends as it does to their inspiration. Tolkien was grievously aware that the songs of Asgard and its everlasting war with the giants, sung for a thousand years or more, survive today only in half-garbled fragments. A single 13th-century verse manuscript, the Poetic Edda, contains the sole shreds — and even that lacks several pages at the very climax of Sigurd’s story. It was his yearning for the irretrievable ur-myths that compelled Tolkien, during the Great War, to begin his own ‘Book of Lost Tales’, later The Silmarillion. Sigurd is absent because this ‘legendarium’ is set far deeper in the past and has its own Elvish nomenclature. But his features are clearly visible in Túrin, the brooding, doomed Silmarillion hero who takes centre-stage in 2007’s posthumous The Children of Húrin. And in the two sequential poems which make up Sigurd and Gudrún Tolkien sets Middle-earth aside to tackle Sigurd’s tale straight on.

| “Sigurd is absent from Tolkien's legendarium, but his features are clearly visible in Túrin, the brooding, doomed Silmarillion hero” |

The plot runs from creation to doomsday, but at its core is the story of how the dauntless Sigurd — also the model for Wagner’s Siegfried — kills the dragon Fafnir, wins his accursed treasure, and is fatally embroiled with two women, the battle-loving valkyrie Brynhild and the Germanic princess Gudrún. After telling how the gold acquired its curse and came to Fafnir, Tolkien recounts the disasters which have overwhelmed Sigurd’s forebears, earthly descendants of Odin. Variously butchered, devoured, poisoned or immolated, the family scarcely needs a curse. Sigurd achieves a more palpably tragic stature due to his courage and honour, his rise from fatherless dispossession to high esteem, and his romantic entanglements.

The key question for Tolkien — one which troubled many trench veterans — is why the bravest and best must die before their time. To answer this he adapts the prophecy of Ragnarok, in which the world will be destroyed yet replaced by a new one purged of evil. In a crucial interpolation, Tolkien makes this renewal contingent on Sigurd, whose tragic death is required so that he can lead Odin’s host of warriors in the final battle: ‘If in day of Doom / one deathless stands / who death hath tasted / and dies no more, / the serpent-slayer, / seed of Odin, / then all shall not end, / nor Earth perish.’

The key question for Tolkien — one which troubled many trench veterans — is why the bravest and best must die before their time. To answer this he adapts the prophecy of Ragnarok, in which the world will be destroyed yet replaced by a new one purged of evil. In a crucial interpolation, Tolkien makes this renewal contingent on Sigurd, whose tragic death is required so that he can lead Odin’s host of warriors in the final battle: ‘If in day of Doom / one deathless stands / who death hath tasted / and dies no more, / the serpent-slayer, / seed of Odin, / then all shall not end, / nor Earth perish.’

Unlike his friend C.S. Lewis, Tolkien refused to make his fantasies ciphers for his religion. Yet the redemptive self-sacrifice of Gandalf and Frodo always had a Christian flavour, and in Sigurd and Gudrún he hints at parallels between Sigurd and Christ as harrower of hell and slayer of that other dragon, Satan. He once told Lewis that every myth was ‘a splintered fragment of true light’; here, he imagines how the grim Teutonic mind might have visualised a world-saviour. The outlook is ineffably stoic: ‘Fate none can flee. Faith man can hold.’

Even with an introductory lecture by Tolkien and explanatory notes by his son Christopher, the two long poems comprising Sigurd and Gudrún are not an easy read first time round because they skip key developments as if the plot were already familiar. But as a full version of the story in its native style, they could hardly be bettered. The language is austere and aphoristic. Phrases repeat like motifs in an illuminated manuscript. The tone is ominous, the cadences sonorous, as if for chanting aloud.

Fans whose tastes do not stretch further than hobbits will be uncomfortable in this murky world of vengeful warriors and witch-women. Yet these same features, together with Tolkien’s bold imagery, his unmatched skill as an alliterative revivalist, and his mastery of a poetic language that is both archaic and direct, will appeal strongly to readers already haunted by the deeper, more sombre musics of Middle-earth.

© John Garth 2009.

The Worlds of

J.R.R. Tolkien

UK hardback

US hardback

To buy in French, Russian, Czech, Spanish, Italian, Finnish, Hungarian, German, or another language

see links here

Buy

Tolkien and

the Great War

UK paperback/ebook

US paperback/ebook

Audiobook read by

John Garth

Amazon UK, Audible UK,

Audible US

To buy in Italian, German, French, Spanish or Polish,

see links here

Buy

Tolkien at

Exeter College