John Garth

Middle-earth sprang to life during the First World War, and the two were entwined from the beginnings of Tolkien’s mythology. In Tolkien and the Great War, I piece together how this stood just before he went off to fight in the Battle of the Somme in summer 1916 – and in The Book of Lost Tales which he began straight after the battle. The impact of war and of battle itself are clear.

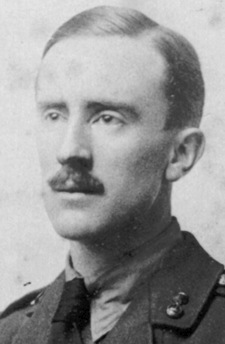

Tolkien in army uniform in 1916, when Middle-earth was brewing

Tolkien in army uniform in 1916, when Middle-earth was brewing

War intrudes into Tolkien’s earliest mythology, even as it stood in March 1916 after a year or more of development, and just prior to the Battle of the Somme.

Makar the battle god seems to have been one of the first named Valar, or gods, in Tolkien’s lexicon of his invented Elvish language ‘Qenya’. But Melko (who in The Silmarillion is called Melkor Morgoth, overlord even to Sauron the Great) does not yet appear.

Particularly striking is how Qenya at this stage equates Germans with barbarity. Kalimban is ‘“Barbary”, Germany’; kalimbarië is ‘barbarity’, kalimbo is ‘a savage, uncivilized man, barbarian. — giant, monster, troll’, and kalimbardi is glossed ‘the Germans’. There is a strong sense of disillusionment in these definitions, so devoid of the attraction which Tolkien had felt towards ‘the “Germanic” ideal’ as an undergraduate (Letters 55). He lived in a country wracked with fear, grief and hatred, and by now people he knew had been killed by Germans.

Almost all of Tolkien’ early conceptions fit the idea that the mythology takes place in the ancient world (kasien ‘helm’, makil ‘sword’). However, some of it smells distinctly 20th-century. Taking the lexicon as a whole (including phases post-Somme), one could easily enumerate features of the trenches: londa- ‘to boom, bang’, qolimo ‘an invalid’, qonda ‘choking smoke, fog’, enya ‘device, machine, engine’, pusulpë ‘gas-bag, balloon’. Entirely anachronistic is tompo-tompo, ‘noise of drums (or guns)’: an onomatopoeia, surely, for the deep repercussive boom and recoil of heavy artillery, but not, one would think, a word Tolkien could use in his faëry mythology. We may be reminded, too, of the terrifying ‘doom, doom’ of the drums in the deep in Moria.

Before the Somme, Tolkien wrote poetry in which war is hinted at symbolically if at all. But straight after the Somme, in hospital and convalescing with trench fever, Tolkien wrote ‘The Fall of Gondolin’ — the first ‘lost tale’ of Middle-earth. It reverberates to his collision with war. Here Tolkien’s mythology becomes for the first time what it would remain: a mythology of the conflict between good and evil. The idea that the conflict would be perpetual came directly from his sceptical view of the bland optimism about the Great War, as Tolkien recalled nearly half a century later: ‘That, I suppose, was an actual conscious reaction from the War — from the stuff I was brought up on in the “War to end wars” — that kind of stuff, which I didn’t believe.”

The Elves of ‘The Fall of Gondolin’ are not the diminutive winged things of Shakespearean and Victorian tradition — they are much more like the Elves as we know them from The Lord of the Rings: tall, heroic, superhumanly able.

This is one of Tolkien’s most sustained accounts of battle. But Gondolin under attack is not the Somme, despite its corpse-choked waters and smoke-filled claustrophobia. Least of all does the tale dress up the English as Elves and the Germans as Goblins. Where, prior to the Somme, Tolkien had defined the monster/barbarity words kalimbardi, etc., to include the Germans, now he removed Germany from the equation with barbarism and the monstrous. Tolkien later insisted there was no parallel between the Goblins he invented and the Germans he had fought, declaring, ‘I’ve never had those sort of feelings about the Germans. I’m very anti that kind of thing.’

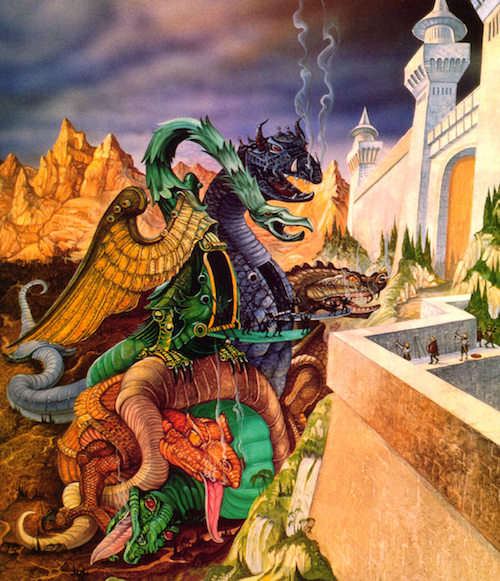

It is only now that Melko appears in Tolkien’s mythology, representing the tyranny of the machine over life and nature, exploiting the earth and its people in the construction of a vast armoury. Orcs and Balrogs are not enough to achieve the destruction of Gondolin. ‘From the greatness of his wealth of metals and his powers of fire’ Melko constructs a host of ‘beasts like snakes and dragons of irresistible might that should overcreep the Encircling Hills and lap that plain and its fair city in flame and death’. The work of ‘smiths and sorcerers’, these forms violate the boundary between mythical monster and machine, between magic and technology. The bronze dragons in the assault move ponderously and open breaches in the city walls. Fiery versions are thwarted by the smooth, steep incline of Gondolin’s hill. But a third variety, the iron dragons, carry Orcs within and move on ‘iron so cunningly linked that they might flow ... around and above all obstacles before them’; they break down the city gates ‘by reason of the exceeding heaviness of their bodies’ and, under bombardment, ‘their hollow bellies clanged ... yet it availed not for they might not be broken, and the fires rolled off them’.

The Fall of Gondolin, as visualised by Roger Garland in keeping with Tolkien’s earliest conceptions. Note the troops emerging from the dragon-creatures. © Roger Garland

The Fall of Gondolin, as visualised by Roger Garland in keeping with Tolkien’s earliest conceptions. Note the troops emerging from the dragon-creatures. © Roger GarlandThe more they differ from the dragons of mythology, the more these monsters resemble the tanks just unleashed for the first time ever on the Somme. One wartime diarist noted with amusement how the newspapers compared the tanks with ‘icthyosaurus, jabberwocks, mastodons, Leviathans, boojums, snarks, and other antediluvian and mythical monsters.’ Max Ernst, who was in the German field artillery in 1916, enshrined such comparisons on canvas in his iconic surrealist painting Celebes (1921), an armour-plated, elephantine menace with blank, bestial eyes. The Times trumpeted a German report of this British invention: ‘The monster approached slowly, hobbling, moving from side to side, rocking and pitching, but it came nearer. Nothing obstructed it: a supernatural force seemed to drive it onwards. Someone in the trenches cried, “The devil comes,” and that word ran down the line like lightning. Suddenly tongues of fire licked out of the armoured shine of the iron caterpillar ... the English waves of infantry surged up behind the devil’s chariot.’ The Times’s own correspondent, Philip Gibbs, wrote later that the advance of tanks on the Somme was ‘like fairy-tales of war by H.G. Wells’.

In ’The Fall of Gondolin’, with a brutal inevitability, the Elves with their medieval technology lose the contest. Tolkien’s myth underlines the almost insuperable efficacy of the machine against mere skill of hand and eye.

These excerpts and adaptations from Tolkien and the Great War include aspects of a reconstruction based primarily on the Qenya lexicon (Parma Eldalamberon 12: Qenyaqetsa: The Qenya Phonology and Lexicon, ed. Christopher Gilson, Carl F. Hostetter, Patrick H. Wynne, Arden R. Smith).

Text © John Garth 2003, 2014. All quotations from the works of J.R.R. Tolkien © The Tolkien Trust / The J.R.R. Tolkien Copyright Trust 2003. The later quotation about the Germans comes from an interview with Philip Norman in the Sunday Times Magazine, 15 January 1967. Artwork reproduced with permission of Roger Garland.

The Worlds of

J.R.R. Tolkien

UK hardback

US hardback

To buy in French, Russian, Czech, Spanish, Italian, Finnish, Hungarian, German, or another language

see links here

Buy

Tolkien and

the Great War

UK paperback/ebook

US paperback/ebook

Audiobook read by

John Garth

Amazon UK, Audible UK,

Audible US

To buy in Italian, German, French, Spanish or Polish,

see links here

Buy

Tolkien at

Exeter College