Tolkien’s gift

John Garth

This article was originally published as an op-ed in the Evening Standard on 12 December 2003. The previous day the final part of Peter Jackson's movie version of The Lord of the Rings had its world premiere. The following day the book itself won the BBC's Big Read vote for the U.K.'s best-loved book.

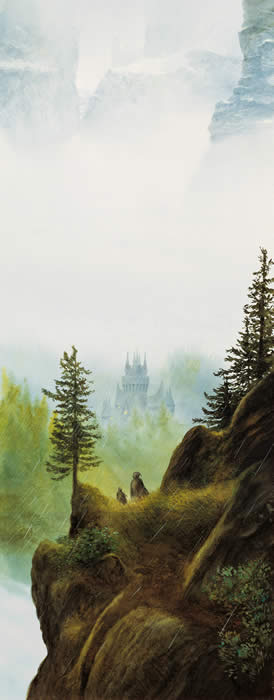

“Tolkien’s gift to us is his love for older traditions. He has jogged the world’s memory” “Descent to Rivendell” © John Howe |

The Lord of the Rings must be one of the most comprehensively dismissed books ever written. Critics have queued up since its publication nearly 50 years ago to denounce it. But J.R.R. Tolkien’s story has outlived one generation of critics, and will certainly outlive another. The coming week will see it doubly celebrated.

Not only does The Return of the King open at cinemas on Wednesday, completing Peter Jackson’s movie version, but Tolkien’s work looks set to take the crown of the BBC’s Big Read vote to decide the nation’s most popular book.

Of all the novels written in the last century, it now seems one of the most likely to be read for both entertainment and enlightenment in centuries to come. Like Homer’s Odyssey, it is for all time.

Why is it such a great and lasting work? Because Tolkien’s story bestrides the chasm between the ancient world and ourselves. His Middle-earth and the modern world are twins, born at the same time, in the First World War.

Modernism, with its experiments with form and its contemporary social focus, emerged then as the dominant literary mode of the 20th century. Modernists such as T.S. Eliot and James Joyce, and war poets like Robert Graves and Wilfred Owen with their accounts of incapacitated suffering, set the tone for what was subsequently considered to be valuable writing.

Originally rejected as an outsider in this literary world, Tolkien has suffered the fate ever since of being deemed beneath consideration.

The author only acquired a wide audience nearly two decades after the Great War, with The Hobbit, a deceptively simple children’s adventure yarn. And nearly two decades later again came The Lord of the Rings, and its summary dismissal by critics such as Edmund Wilson, who called it “juvenile trash”.

How could they have got it so wrong? Tolkien knew what they did not — the power of story to ingrain itself in the heart. He acknowledges this in The Lord of the Rings, when his hero strays into an enchanted wood. “When he had gone and passed again into the outer world, still Frodo the wanderer from the Shire would walk there, upon the grass among elanor and niphredil in fair Lothlórien.”

“Tolkien knew what his detractors did not — the power of story to ingrain itself in the heart” “Tolkien knew what his detractors did not — the power of story to ingrain itself in the heart” |

Many pundits seem not to have absorbed very much of the book at all. It has to be doubted whether some have even made it past the opening chapters, with their hobbit parties and satirical whimsy.

But even when they have read on, critics have used the wrong yardstick to measure Tolkien’s worth. Intoxicated by modernism and its claim exclusively to represent the modern world, they have simply forgotten the value of other modes of storytelling.

Tolkien’s gift to us is his love for older traditions, particularly the epic and the fairy tale, which he transformed with a masterly hand into a narrative for his own time. He has jogged the world’s memory.

He once said that his love of fairy tale was woken to full life by war, meaning that it was only here that he discovered the literary

reflection of all war’s fantastical horrors and its transfigurations of ordinary men into something like heroes.

The epic mode sets him on a high seat overlooking the mechanised slaughterhouse of the Somme, so that he could see the First World War not as a conflict between belligerent nations, but as one skirmish in the ongoing attempt by “civilisation” to

enslave the human spirit and the natural world for material gain. In contrast to the classic Great War poets, with their vivid close-ups, Tolkien had started to make sense of the chaotic shambles of the war years.

From a broader perspective, the irony of life in the static front lines revealed not only suffering, but also the ennoblement of the individual. All this Tolkien poured into The Lord of the Rings.

Peter Jackson deserves credit for bringing an even wider audience to these themes, and for translating those epic and fairytale modes onto the screen for the first time successfully. But anyone tempted to watch the films in order to pass judgment on Tolkien’s story without reading the book should beware.

Jackson is prone to elaborate and exaggerate. In doing so, he squanders many of Tolkien’s finest gems, mangles important plot lines and abandons the delicate restraint which allows this complex literary fantasy to maintain its lasting grip on the reader.

| “In his story of marvels, the most marvellous thing is the human spirit, often foolish and vain but also tenacious and generous to the point of self-sacrifice” |

Tolkien’s power does not lie simply in imaginatively repeopling the world with elves and dwarves, or even in introducing hobbits and the tree-herding ents. In his story of marvels, the most marvellous thing is the human spirit, often foolish and vain but also tenacious and generous to the point of self-sacrifice. The spirit is tested in a world not so different from our own, in which each element of fantasy relates to reality as if part of a huge symbolist tapestry.

Like all great artists, Tolkien has not only drawn the world around him: he has altered it. Today, millions of readers carry his landscapes, characters, incidents and themes in their thoughts as they go about their day-today lives.

His story of the changing world, in which loss and death are inevitable, celebrates all that is in danger of being swept away. In a world so despairing and disenchanted, he has succeeded in reminding us of hope and enchantment.

If his book takes the crown at the Big Read tomorrow, it is not because of any imagined orchestration of votes by his hardcore fanbase, but because he has found a quiet and a lasting place to dwell inside millions of readers.

© Evening Standard 2003. Reproduced with permission. “Descent to Rivendell” reproduced with permission of John Howe.

The Worlds of

J.R.R. Tolkien

UK hardback

US hardback

To buy in French, Russian, Czech, Spanish, Italian, Finnish, Hungarian, German, or another language

see links here

Buy

Tolkien and

the Great War

UK paperback/ebook

US paperback/ebook

Audiobook read by

John Garth

Amazon UK, Audible UK,

Audible US

To buy in Italian, German, French, Spanish or Polish,

see links here

Buy

Tolkien at

Exeter College