John Garth

The Oxford English Dictionary, published by Oxford University Press – the University’s largest department – is embracing digitisation and leaping forward.

This article first appeared in the July 2013 issue of Blueprint, the University of Oxford staff magazine.

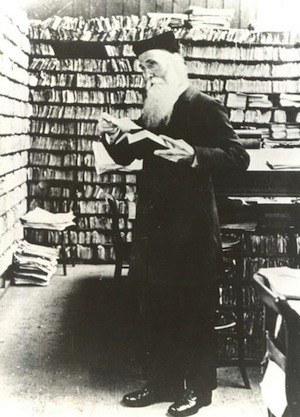

Old-style lexicography: the OED’s first editor, James Murray, in his scriptorium

Old-style lexicography: the OED’s first editor, James Murray, in his scriptoriumIn 1879 James Murray, the first editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, foresaw four volumes, taking 10 years; in fact the complete Dictionary was only published in 1928, occupying 10 massive volumes. Yet Murray’s error was purely quantitative. Sitting in his famous ‘scriptorium’ marshalling slips of quotations, he could never have imagined the qualitative quantum leap the Dictionary has since taken – becoming a doorway into a lexical world accessible from desks and laptops globally.

‘What the OED was in the 19th century was a book where you could look something up, you found what you wanted, and you went away’, explains Chief Editor John Simpson, a Fellow of Kellogg College, Oxford, who retires in October (handing over to Michael Profitt, current Editorial Director). ‘It’s now a major hub from which people move to gain insights on language, or texts, or whatever. It’s working on a different dimension.’

The Dictionary has always aimed to record not only the current language, but also its history, with etymologies, shifts in usage, and quotation evidence. But how could a laboriously compiled book capture something as protean as English? A one-volume 1933 Supplement and a four-volume Second Supplement (1972–86) seemed to augur endless incremental additions, with ease-of-use declining at every step. When Simpson joined OUP’s cross-dictionaries New Words team in 1976, the OED seemed obsolescent.

| “What the OED was in the 19th century was a book where you could look something up. It's now a major hub from which people move to gain insights on language... It's working on a different dimension” |

‘There just wasn’t an elegant solution for the Dictionary until we started to look at the significance of putting the data on computer’, he says. The entire text was input, tagged, and re-sorted to create the Second Edition – 20 volumes in 1989 and a single CD-ROM in 1992. But this was merely ‘a halfway house’.

It is the Third Edition that has really begun to exploit digitisation and the web – still in its infancy when Simpson took charge of the Dictionary in 1993. Now readers can cross-refer across the 600,000-word lexicon instantaneously. Staff can edit any entry as need arises, and the whole database is uploaded afresh every three months. OED Online is a work in progress in which the Second Edition is gradually being replaced by the Third. All else being equal, Simpson predicts it will take about 25 more years.

New words – researched by a team of about 10 lexicographers – also form a resource shared across OUP’s dictionaries. Such is the thoroughness of the OED that a new word is often published first at Oxford Dictionaries Online – a free dictionary, grammar, blog and general shop window for OUP lexicography, launched in 2010. At the OED, others among the 70 lexicographers focus on rewriting the etymologies, on scientific words, and on bibliographical issues.

For new citations and other language information, Oxford dictionaries do not look to Google but to their own databank of about 2.5bn words and rising, the Oxford English Corpus, which is compiled by computational linguists drawing on web content. ‘It’s trying to rebalance a rather unbalanced web, whose language tends to be dominated by the activities that we do online, such as shopping’, says Judy Pearsall, Editorial Director of OUP’s Global Academic Division.

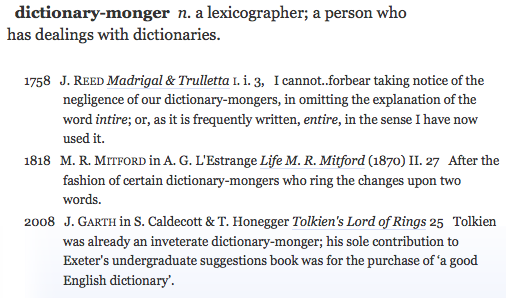

Word up: For my reviews ofThe Ring of Words, about Tolkien and the OED, and of the OED on CD-ROM, click on the images

Word up: For my reviews ofThe Ring of Words, about Tolkien and the OED, and of the OED on CD-ROM, click on the images

But the proof of the pudding is in the eating (earliest citation William Camden, Remaines, 1605), and the consumer must be brought to the table. Anyone who holds a UK library card can access OED Online for free. Pearsall hopes to find ways of delivering parts of the OED content free more widely.

New words excite the media most – the latest crop includes dad dancing and tweet (as in Twitter). The general user, however, shows a much more varied taste. An interactive feature at the Oxford Dictionaries Online blog allows users to input text of their own to discover ‘How Shakespearean are you?’. Pearsall sees the site becoming ‘the place people go for their language information and then move on for more specialised information’ – to the OED, for example. Many readers reach Oxford Dictionaries Online via search engines after querying a point of grammar or a word definition. And in a world of ever-increasing digital integration, those search engines may themselves be underpinned by lexical information provided by OUP. The Google dictionary is an Oxford one.

The relationship with readers works both ways, with volunteers for the OED helping to hunt down books so obscure that they exist in no known collection, or providing living evidence about words and phrases, for example through television programmes such as the BBC’s 2006–7 Balderdash and Piffle. It seems a thoroughly modern concept – crowdsourcing only entered the OED this June – but it is no different in kind from the use of volunteer book readers to gather the Dictionary’s founding collection of quotations in the two decades before Murray’s appointment.

‘There are people in all sorts of corners of the globe who know about the history of words within their specialist subjects, and those are the people we want to work with’, says Pearsall. A pilot website was set up a few years ago to gather citations from the language of science fiction, and Simpson says the same method would work for sport, archaeology and so on. He thinks OED Online could be wrapped in ‘a wiki overcoat’ – a collaborative, moderated online environment rather like Wikipedia, through which anyone could offer language information and view it all raw, before the lexicographers get to work on it.

Increasingly, the editors are exploiting digital means to provide what no book could ever deliver. If asked the right question, OED Online can tell you everything it knows about the language of computing, or which authors’ works have provided the most citations, or what Italian words have entered the English language and when. It dovetails with the independently compiled Historical Thesaurus of the OED, in which all the various senses of its words are arranged thematically. For those with specialist needs, it also furnishes links to dictionaries of Old and Middle English. The interface is being tailored to provide graphical ways into the data, such as timelines. Simpson, who counts ‘working out how to move it from a Victorian dictionary to a 21st-century dictionary’ as the big achievement of his editorship, would like to see the OED incorporate images and (copyright permitting) sound and video.

Nostalgic bibliophiles may miss the feel of paper and the grand bindings of the print volumes. Thanks to digitisation, however, the OED is truly unbound, in the best possible sense of the word.

John Garth is cited in OED Online. See more...

John Garth is cited in OED Online. See more...• Read more about the OED and free access to its content here.

• The full July 2013 issue of Blueprint can be downloaded as a free pdf here.

Article text © John Garth 2013. Reproduced with permission of the Public Affairs Directorate, University of Oxford.

The Worlds of

J.R.R. Tolkien

UK hardback

US hardback

To buy in French, Russian, Czech, Spanish, Italian, Finnish, Hungarian, German, or another language

see links here

Buy

Tolkien and

the Great War

UK paperback/ebook

US paperback/ebook

Audiobook read by

John Garth

Amazon UK, Audible UK,

Audible US

To buy in Italian, German, French, Spanish or Polish,

see links here

Buy

Tolkien at

Exeter College